Welcome to another edition of the Struggle.

The Struggle is a bi-weekly newsletter where I share my thoughts and learnings from running a startup in Southeast Asia.

A week ago, I was part of a panel discussion where many of the attendees asked questions about what steps you need to take if you have aspirations to run a startup someday.

It’s kind of hard to summarize everything that comes to mind on the topic. While I wish there are some shortcuts to go through, unfortunately, I do not think that’s possible.

Whether it’s your first startup or you have been through that process in the past, the learning curve is typically pretty steep.

In turn, many people advise to focus on learning the most popular models in entrepreneurship, such as the lean startup, business model canvas, validation board, design thinking, and other similar frameworks. Assuming that such frameworks will provide all the necessary knowledge to be successful. While such models definitely help, that’s wishful thinking.

I was that person myself.

Back in 2013, after completing management training in a hotel located in Taiwan, I was questioning if a career in hospitality is truly what I want to do. Given that I spent seven years working for large hotel chains, I felt comfortable with my knowledge and career opportunities. Yet, I did not think that I am truly passionate about it.

As I reflected on what to do next, I moved back to Denmark to continue my Master's studies while figuring out what’s next.

Going back to the university campus, I had exposure to several entrepreneurship events/hackathons that opened my mind to the world of startups and tech.

Naturally, the first thing I did, was to learn inside out all startup-related frameworks mentioned above. I devoured books on the topic, attended every single event, and joined local startup communities.

In the process, I solidified my understanding of how to use models like the lean startup, how to build a business model canvas, and in general, how to design hypotheses and test them out.

Understanding how to apply those models across different business models gave me a great understanding of what’s important conceptually to run a business. But, still, with that, I got the illusion that I truly understand how to launch and run a startup. After all, I thought that I was able to master the best tools out there.

Knowledge fallacies

The outcome was that I fell victim to common knowledge fallacies.

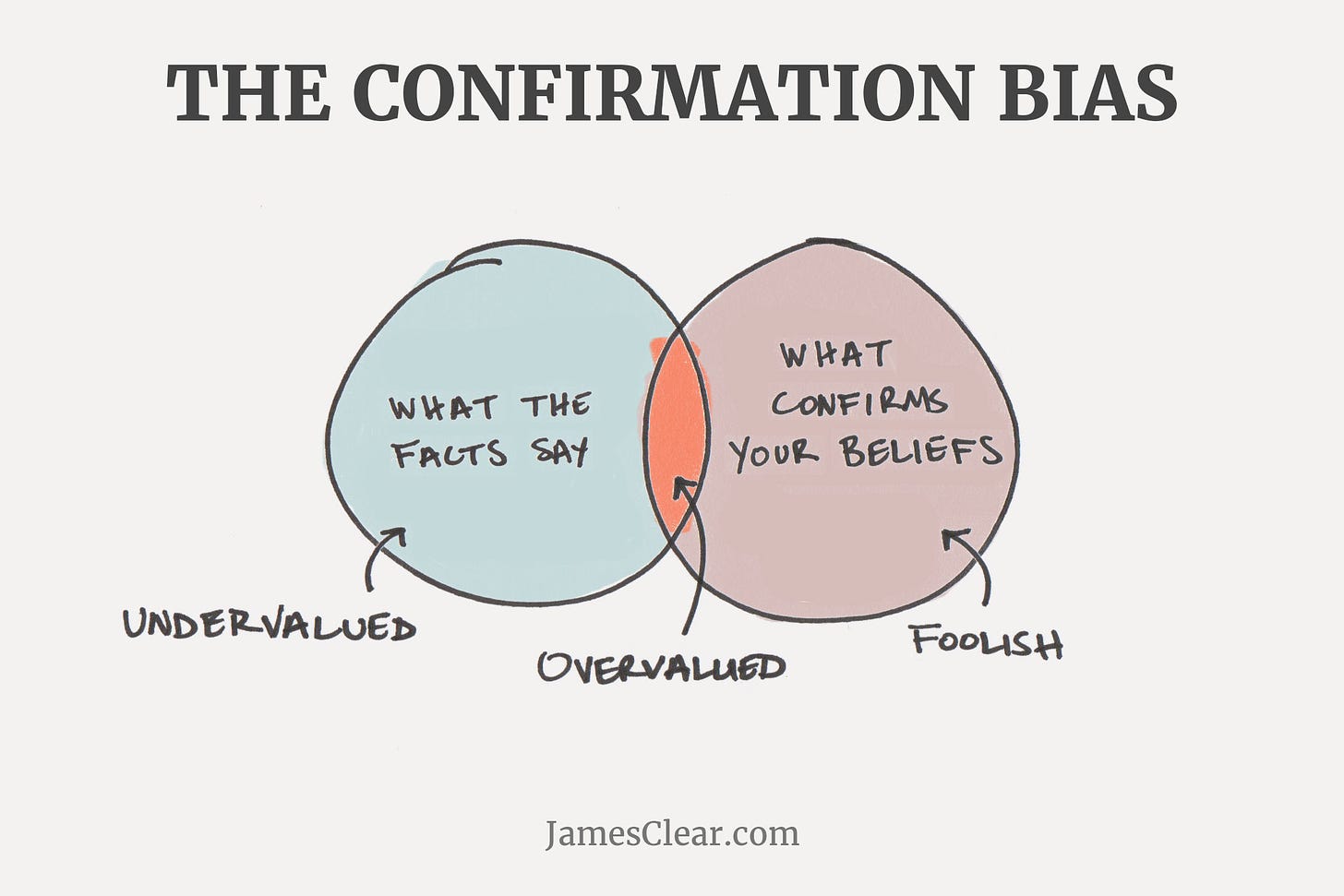

Confirmation bias

Nicely summarized by these two quotes:

“Confirmation bias is our tendency to cherry-pick information that confirms our existing beliefs or ideas. Confirmation bias explains why two people with opposing views on a topic can see the same evidence and come away feeling validated by it.”

Confirmation Bias And the Power of Disconfirming Evidence by f6.blog

"Most people don’t want accurate information, they want validating information.

Growth requires you to be open to unlearning ideas that previously served you."

5 Common Mental Errors That Sway You From Making Good Decisions by James Clear

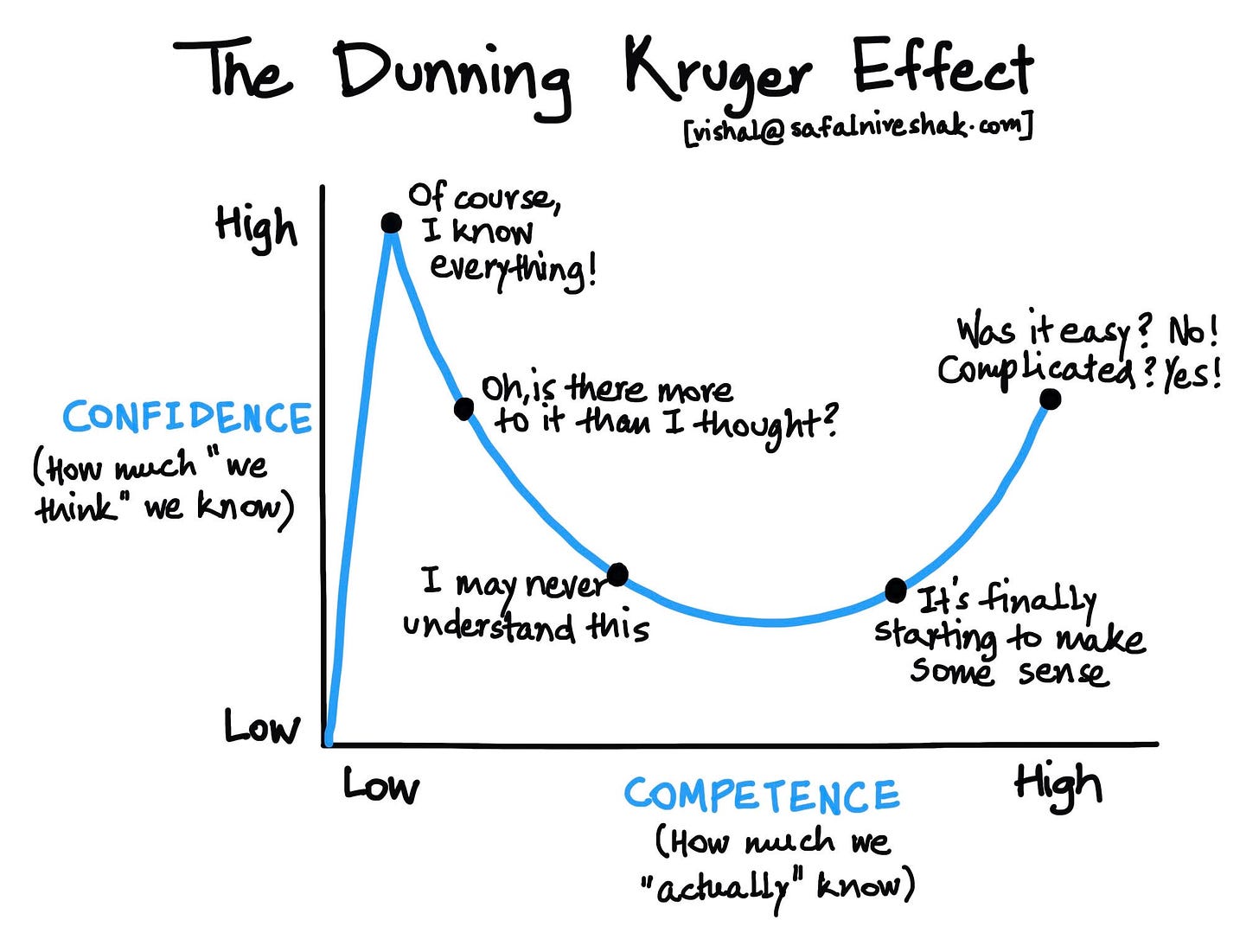

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

“when we gain a little bit of knowledge this can become a dangerous area. Those who have a little bit of experience have greater confidence in the understanding that they “know it”. As we gain more knowledge our confidence dips dramatically. Until we actually have that in-depth knowledge then our confidence is restored, although not as high as it was when we didn’t know it!”

Cognitive Biases — Dunning–Kruger effect by Michael Gearon

To illustrate the Dunning-Kruger effect, consider the following drawing:

When I was starting my first business, I had a lot of confidence but very little competence. Some people refer to that state as mount stupid.

Over time, I learned that running a startup is a lot more complicated than it seems at first glance. Starting a new venture is one of the most difficult things you may end up doing.

Looking back at my experience, learning the most popular frameworks was instrumental in some early wins, like winning many startup competitions. But, unfortunately, those were vanity metrics. While that was well-intentioned, it led me directly to mount stupid.

Add a layer of subconscious confirmation bias, and you see how it’s easy to score very high on how much you think you know vs. how much you actually know.

I spent a fair bit of time on mount stupid, deluding myself about what I think I know. Luckily, at some point, I reached the tipping point and started realizing how there is a lot more to learn than what I knew at the time.

Here I would like to make a disclaimer, learning the fundamentals in each domain is not wrong.

Given my experience, learning lean startup and other similar frameworks was most definitely helpful.

Yet, my point is that there are no shortcuts to pivoting a career. Understanding conceptually how a business operates, speaking the industry's jargon, having the knowledge to apply relevant frameworks, and following the latest news are great first steps. But it takes a lot more before you can develop sufficient knowledge in a new domain.

Jeff Bezos has a great way to articulate that using the concept of “it’s always Day 1”:

“By retaining a Day 1 culture—one that is customer-obsessed, that enables high-quality and high-velocity decision-making, and that empowers employees and leaders alike to stay curious, be experimental, and permit failure and the learning that comes with it as a competitive advantage rather than a risk to avoid at all costs—a company is better able to leverage its growth rather than be slowed down by it. And is better suited to lead innovation at the forefront.”

Elements of Amazon’s Day 1 Culture by Dan Slater

To me, Day 1 represents a mindset of being humble, of acknowledging that you have done a lot, yet there is a lot more ahead of you.

Embracing the Day 1 mentality is a great tool for fighting confirmation bias and better understanding where you are on the Dunning- Kruger’s Effect chart.

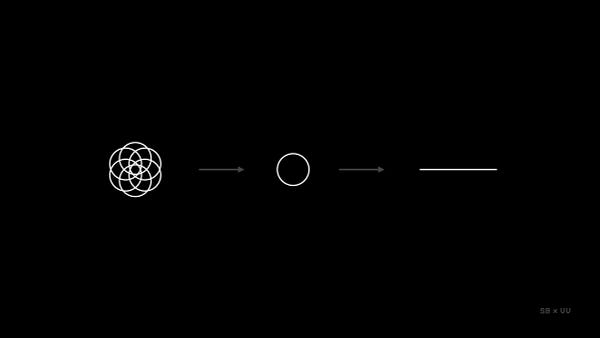

Another great way to overcome knowledge fallacies is to adopt reasoning from the first principles.

Reasoning from first principles

As the tweet suggests, reasoning from first principles, also known as first principles thinking, is about thinking like a scientist.

Break down complicated problems into the most fundamental elements to get a deeper understanding of the issue at hand. By doing that, you are not relying on known facts or what is considered common sense in your industry/line of work.

As kids, we often ask a ton of questions, to the extent that our parents start answering with “because I said so” or “you are too young to understand.”

Often that stems from their inability to explain complex concepts in an easy-to-understand way or because they had enough explaining done for the day.

As we get older and become more aware of ourselves, we want to avoid being embarrassed in public. Hence, we reduce the number of questions we ask and end up agreeing with whatever seems to be common wisdom. That’s especially pronounced in Asian cultures, where the fear of losing face in public is terrifying.

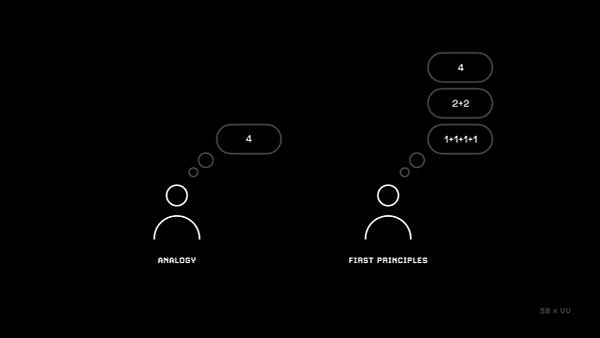

We start borrowing many analogies, which helps us to 1) avoid asking stupid questions (save face), 2) it’s easier to communicate complex ideas through analogies. Essentially, the alternative of thinking through analogies is reasoning from first principles.

Rather than assessing a problem thoroughly, breaking it down into its most basic elements, we end up agreeing with what other people believe to be true.

We outsource our thinking.

There are pros and cons to outsourcing your thought process. On the one hand, borrowing analogies makes it easier to have a complex conversation. By doing that, you spend less mental energy on understanding difficult problems coming your way.

On the other hand, we limit our beliefs of what’s possible.

That’s especially pronounced when building a startup. After all, a startup is essentially an attempt to solve a problem in a repeatable and scalable way. To truly, solve a problem that presumingly does not have a solution yet, the founders must understand inside out the problem and attack it with thousands of iterations and improvements.

Elon Musk is perhaps today’s most popular entrepreneur who consistently reasons from first principles to redefine what’s possible.

Consider the following example:1

“Somebody could say — and in fact people do — that battery packs are really expensive and that’s just the way they will always be because that’s the way they have been in the past. … Well, no, that’s pretty dumb… Because if you applied that reasoning to anything new, then you wouldn’t be able to ever get to that new thing…. you can’t say, … “oh, nobody wants a car because horses are great, and we’re used to them and they can eat grass and there’s lots of grass all over the place and … there’s no gasoline that people can buy….”

… they would say, “historically, it costs $600 per kilowatt-hour. And so it’s not going to be much better than that in the future. … So the first principles would be, … what are the material constituents of the batteries? What is the spot market value of the material constituents? … It’s got cobalt, nickel, aluminum, carbon, and some polymers for separation, and a steel can. So break that down on a material basis; if we bought that on a London Metal Exchange, what would each of these things cost? Oh, jeez, it’s … $80 per kilowatt-hour. So, clearly, you just need to think of clever ways to take those materials and combine them into the shape of a battery cell, and you can have batteries that are much, much cheaper than anyone realizes.”

First-principles thinking is not a sustainable approach if applied in every situation because it requires a lot of mental energy and research. Yet, if applied when working on big problems, it can be the difference between training horses to run faster or building a car.

Exercising that muscle so that you can easily break down complex concepts into their fundamentals is definitely a wise use of one’s time.

In turn, applying first principle thinking to new domains can, in fact, accelerate your ability to understand complex fields like tech startups truly. Think of how Elon Musk entered two of the world’s most complex fields - electric vehicles and sending rockets to space. There were many common beliefs about both fields regarding what’s possible, but thinking through first principles allowed him to cut through the noise and build incredibly valuable companies. Today, his projects take on almost every major sector, solving some of the world’s biggest problems.