Welcome to another edition of the Struggle.

The Struggle is a bi-weekly newsletter where I share my thoughts and learnings from running a startup in Southeast Asia.

Ever since I started working in tech, it feels like I have been drowning in information.

Answering emails, paying attention to conversations on social media, reading data from various analytics tools, listening to insights from colleagues, and keeping up to date with the amazing content the internet has unleashed is not an easy task.

In today’s knowledge economy, and especially when working at a startup, things simply move really fast.

In the early days of most startups, there aren’t many people and processes. In turn, information flows quickly. As a business leader, you need to make many decisions across different departments, even when you are not necessarily an expert in those fields.

To truly make an educated decision, we need to focus on the problem at hand, understand the circumstances, observe immediate feedback, experiment, review learnings, and only then make decisions. That requires time and attention, two rare commodities.

Unfortunately, given everything else happening, it’s tough to slow down and make educated decisions at all times. Consider the following quote by Reid Hoffman:

“Every growing startup is surrounded by fires — whether issues of product, market, competition, or operational scalability. Smart entrepreneurs don't try to fight every fire. Instead, they figure out which fires they can let burn — so they can focus on the ones they absolutely have to fight. It's a delicate balance, because if you let fires go on too long, you'll get burned.”1

Your ability to understand which fires to focus on becomes paramount.

In my experience, a powerful solution here is to simplify the complexity we are facing by developing (or borrowing) relevant mental models.

I have always been fascinated by mental models. Some time back, I started collecting the most impactful frameworks that help me make decisions in today’s fast-paced and ever-changing environment.

In the course of several essays, I will be sharing the mental models that have worked well for me. In fact, I already started documenting a few of them, the most recent one being Google’s framework on how to promote people. Read Newsletter 57 featuring The Problem, Solution, How, Execution (PSHE).

What is a mental model?

James Clear, the author of Atomic Habits, wrote a great definition here:

“A mental model is an explanation of how something works. It is a concept, framework, or worldview that you carry around in your mind to help you interpret the world and understand the relationship between things. Mental models are deeply held beliefs about how the world works.”

Another definition that I really like comes from a famous speech by Charlie Munger:

“Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience both vicarious and direct on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.”

Why are mental models important?

Whether you are aware of it or not, we have all developed mental models over the years that help us to make decisions fast. The problem is that if you let your subconscious mind dominate your worldview, you will end up explaining every problem you face through that worldview.

“Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters needs pounding.” 2

That’s why you need to consciously develop a tool kit of mental models designed to help you make quick decisions, no matter how much time or information you have. Otherwise, you are risking having a limited set of mental models, resulting in a low probability of making good decisions and solving problems.

Expanding your worldview

There are a few easy ways to identify and employ relevant mental models:

Read a diverse set of books

“If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

Haruki Murakami

Curate your social media newsfeed

Recently, Netflix released the Social Dilemma. The movie steered many discussions around how social media platforms are designed not only to connect but also to manipulate us.

My approach to using social media platforms is to do the opposite, i.e., manipulate the algorithms to work to my liking. It may sound unattainable, but it’s actually pretty easy. All you need to do is to study how the algorithm works by doing a series of experiments. Pay attention to what changes take place when you like, comment, and watch certain content. Identify how much of that you need to do to have visible changes in your newsfeed. Then keep on engaging with what matters to you until you clear out the noise and have only relevant information.

On all platforms that I use (Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram), I have consciously liked, shared, DMed, and followed people that I want to hear more from. In turn, I have nearly full control of my feed, giving me an incredible flow of relevant information from some of the smartest people in my field. In turn, I have access to a synthesized flow of content that I can learn from and apply immediately.

Study the fundamentals of seemingly unrelated fields

Last month, I read a book called Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein. The entire book talks about the benefits of studying different, seemingly unrelated fields. Contrary to the common belief - we all need to be specialists to succeed. Here you go a quote from the book, speaking of the importance of exploring multiple fields:

“Scientists examined the life path of the athletes. Eventual Elite athletes typically devote less time early on to deliberate practice in the activity, which they will eventually become experts. Instead, they undergo what the researchers call a sampling period. They play a variety of sports and gain a range of physical proficiencies. They learn about their own abilities. Only later did they focus on and ramp up practice in one area. Late specialization is the key to success in these cases."

Combining the three strategies mentioned above has undeniably helped me cope with an ever-changing and complicated world. As a result, I am constantly on the lookout for more tactics and perspectives.

“The chief enemy of good decisions is a lack of sufficient perspectives on a problem.”

Alain de Botton

The more sources I draw upon, the easier it gets to develop what people call liquid knowledge.

Liquid knowledge

Liquid knowledge stands for developing knowledge that flows from one topic to the next. Meaning, we should avoid thinking of mental models as isolated frameworks. Instead, to develop true liquid knowledge, we need to consider how different mental models connect.

Rocks, Sand, and Water Framework for Attention

There are thousands of mental models.

I will be covering only the ones that I understand and find useful. Starting with “Rocks, Sand, and Water Framework for Consumer Attention” by Sarah Travel.3

The framework was developed as a way to assess consumer startups competing for attention in a post-covid world.

How does it work?

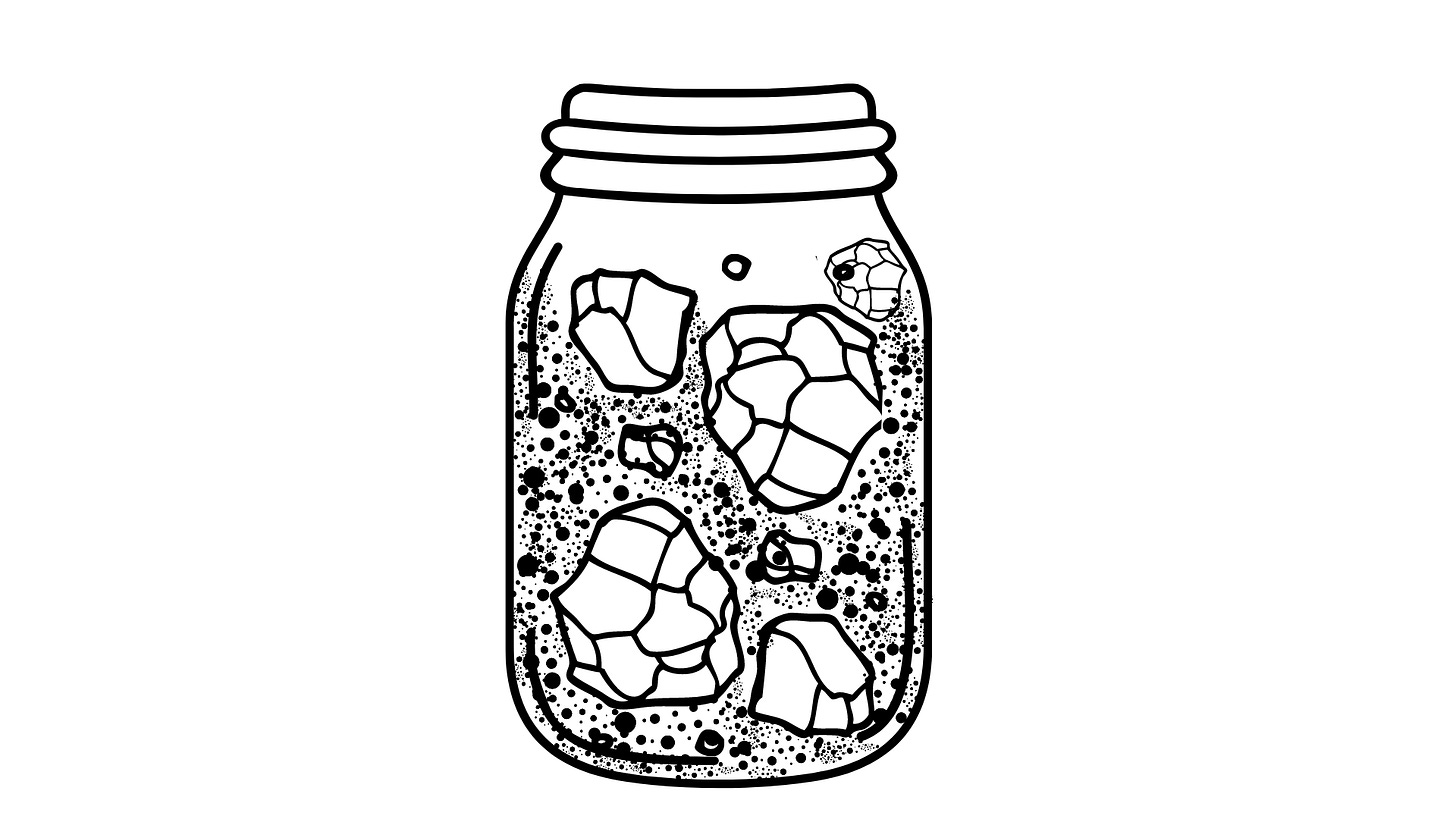

Imagine that a jar represents the 24 hours day we all have. Following that chain of thoughts, the jar can be filled with three types of events:

Rocks - the biggest blocks of time. They are the hardest to fit into one’s schedule and thus the hardest to earn. “Rocks” could be spending time with family, sleeping, eating, major tasks at work, and in some cases, watching TV.

Sand - smaller events that take place during attention gaps between rocks. For example, spending 30 seconds on TikTok, Instagram, chatting on WhatsApp, making quick calls, etc.

Water - “water” can overlay rocks and sand. In turn, water does not require dominant attention, and it can be complementary to other activities. Think of listening to a podcast when driving, listening to music when exercising, audiobooks, etc. Most of the examples I can think of are audio-based activities, but communication via Slack or another similar medium (Discord), as long as it’s not disruptive to your work, can be considered as “water” too.

Now you might be asking yourself, how is that framework useful?

Well, depending on your line of work, you can use it in one of two ways:

Assess your consumer startup concept

Assuming that you are building a product supposed to take over some of the “rocks” in people’s lives. Think about the amount of value your solution will need to provide. To replace a “rock” with another considerably time-consuming activity, it must provide equal or more value.

While that’s relatively easy for some segments of people who may be spending a lot of time watching TV, it’s tough when it comes to most people and replacing their most important activities like sleep, family time, eating, etc.

Consider how you can break some of the “rocks” into “sand” or “water.”

Let’s take the example of reading a book. That’s a long activity that may take a few hours every day until the book is completed. Luckily, thanks to the internet today, we have access to a lot of high-quality content, hence why we can break “a rock” in the following way:

Books → Blogging → Microblogging, Movies/TV → short videos, etc.

In the process, I will optimize my time, as I will have more time for other important activities in my life.

A few things to consider about the “Rocks, Sand, and Water Framework for Attention”:

What is considered a “rock” for some people could be “water” to someone else. Think of the following, the host of a podcast puts a ton of effort into producing one great episode; thus, that’s a “rock” for him. At the same time, all of his listeners consider the same outcome as “water” because of how people consume podcasts.

Unlike “sand” and “rocks,” which compete for attention and are a zero-sum game, water is a positive-sum because it works well with other activities.

While listening to audiobooks and podcasts is considered “water,” they need to have a simple “rock” experience underneath. Think of commuting and exercising, as otherwise, the listening experience can become a “rock” itself.

Activities like COVID are making major shifts in what we consider to be a “rock” and what it is “sand.” For example, we commute less; thus, we have more time for other “rocks” or “sand,” but we do not know if those changes will be lasting or just until we are all vaccinated. Think of how Clubhouse started with a bang and slowly got less trendy.

Key takeaways

Mental models help you make sense of an increasingly complex and fast-paced world.

Invest efforts to study, curate, and ultimately develop a list of mental models to help you eliminate biases while helping you to make high-quality decisions.

If you consider building a consumer startup, spend time thinking about what you plan to replace. Is it a “rock,” “sand,” or perhaps “water”?

Consider what decisions you can make to break or replace unnecessary “rocks” in your life.

Positive-sum activities are ideal because they are complementary to existing habits.

Reid Hoffman, Why the best entrepreneurs let fires burn, available here.

James Clear, Mental Models: How to Train Your Brain to Think in New Ways, available here.

Sarah Travel, The opportunities and risks for consumer startups in a social distancing world, a framework, available here.