Welcome to another edition of the Struggle.

The Struggle is a bi-weekly newsletter where I share my thoughts and learnings from running a startup in Southeast Asia.

As a thought experiment, I will be releasing a few articles breaking down problems I would address if I start a new company tomorrow.

In a continuation of the previous two articles, I am covering industries ripe for disruption. Hand in hand with that, I touch on opportunities to launch new startups in those industries.

Whenever I think of startup ideas, the following tweet by Keith Rabois comes to mind:

It’s so simple yet so true.

First, find a large and fragmented industry with a crappy customer experience, then streamline and control the entire value chain as much as possible.

We have seen vertical integration taking place across various industries in the process, improving customer experience while creating value for shareholders. Think of Amazon, IKEA, Netflix, Apple, to name a few.

Meaning, the business leverages technology to a) integrate supply, demand, and operations and b) builds direct relationships with the end customer to build products and customer experience that result in high customer satisfaction.

“Customers don’t care whose fault it is when something doesn’t work perfectly. Customers care about the overall experience. And unless you control and can dictate the overall experience, you can’t optimize it. So the only way to create an awesome product is to dictate all the specs and all the component pieces. You’re always making compromises if you don’t fully integrate.”

Keith Rabois in an interview for the North Star Podcast

On that topic, I wrote Startup Ideas: Opportunities in Education, describing how education is ripe for disruption due to low NPS scores and outdated processes.

Today I will touch on another massive industry that comes to mind when reflecting on where I have experienced poor customer experiences and little innovation: construction.

The problems with construction

The construction space has interested me for a while. First, the barriers to entry in construction are amongst the highest across all business sectors due to inherited capital expenditures (CAPEX). Second, it is a low-profit margin yet highly competitive sector, and third, it’s hard to reach economies of scale. Despite all that, the opportunity for someone to come in and find a cheaper, more efficient, and customer-centric way of delivering value is massive. The US housing market alone comes at a staggering $33.6 trillion; when trying to estimate the global housing market, the opportunity gets so big that your TAM calculations seem fake 🤯.

My experience with real estate

In late 2017, I got a job as GM at a coworking space in Jakarta, Indonesia. Since I was one of the first employees, my responsibilities covered pretty much everything, including business development, recruitment, operations, project management, and facilities maintenance. At the time, the space was not even completed yet, and while we did have some great people to look after the construction process, I got a front-row seat experience in the inefficiencies of that sector.

When an entrepreneur experiences an inefficient process, it bugs them. Unfortunately, the current construction process is expensive, errors happen all the time, and delays are common. So I spent a lot of time reflecting on why is that happening?

Despite the size of the market and how much importance people give to their homes, we have not seen much innovation compared to other verticals.

Your house is part of your identity and status; in fact, most people can afford to buy just a few properties in their lifetime, which makes the process of picking the right property and designing it to your liking incredibly important.

At the same time, construction projects are well known for being over budget and behind schedule.

“KPMG’s 2015 Construction Survey found just 31% of projects were within 10% of their original budget, and only 25% were within 10% of their original deadline. A literature review in Aljohani 2017 found average overrun rates anywhere from 16.5% to 122%, depending on the type of project being studied.”

Brian Potter, Why It's Hard to Innovate in Construction

To address that, construction sites rely on many project managers to control and prevent mistakes from happening. Unfortunately, most projects are built in relatively unique settings, meaning new construction may occur on a different site. Hence, the weather is often different. Additionally, you may hire new contractors bringing another unknown variable as you do not have prior experience working with them. Even clients differ one from another; some like to be more involved than others, further complicating the project. In addition, unlike in software, a building cannot be released as a prototype or A/B tested to eliminate all potential bugs. Not to mention that failures in construction may end up causing life safety issues, which results in heavy regulations slowing down things further.

In my experience as an outsider, the construction industry is not terribly transparent. We lack the infrastructure to compare adequately different contractors, designers, project managers, and even materials’ costs. Couple that with the industry jargon, and if it’s your first time launching a real estate business / designing your first home, you will probably feel lost and make many mistakes.

“Creating a new building from scratch is extremely complicated. It involves finding and buying land, doing a bunch of legal and environmental due diligence, running market research to confirm the best use, getting entitlements and permits, securing investment and loans, commissioning design and engineering, overseeing construction, calming angry neighbors, doing a brand and marketing strategy to attract tenants, doing background checks, unclogging toilets, and ultimately selling the building to another real estate investor…”

Apt: The Natively Integrated Developer, by Pacy McCormick

Shortly after taking over the coworking business of Greenhouse, I thought that “construction does not have a culture of innovation” or “construction is too traditional.”

But today, I wonder, is that truly the case. Given the sector's complexity, potential safety issues, and how software is eating the world, is it possible to solve all those problems?

Productizing construction

It turns out yes, it is possible, and many exciting startups are popping up to address the inefficiencies mentioned above.

The solution seems to be productizing the space to break it down into smaller, easier to understand and deliver solutions.

Consider the following few examples of companies innovating in and productizing the construction industry.

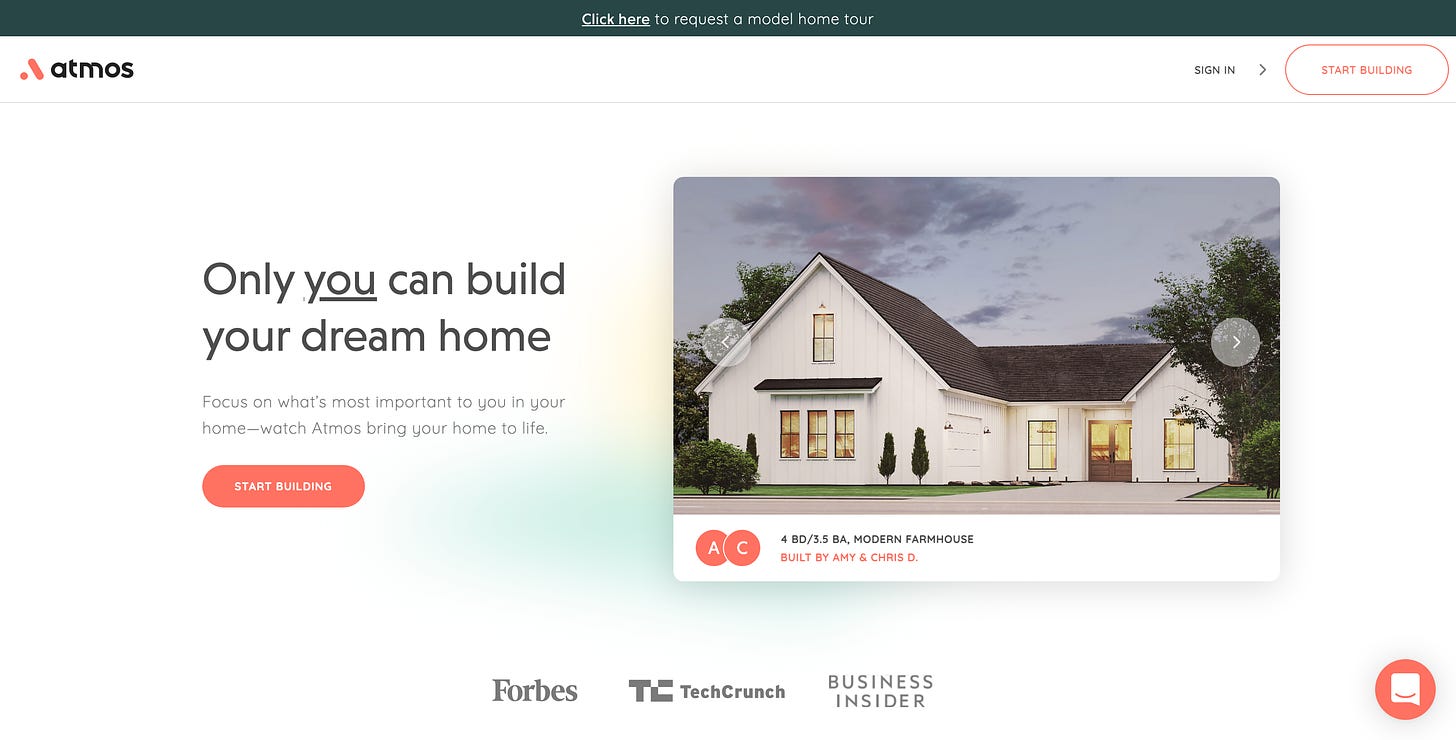

Atmos has removed all the uncertainty and lack of transparency in buying, designing, and building your next home. Instead, the experience is intuitive and considers your hobbies, budget, and design preference. For example, you start by picking a land taking into account the proximity to the city of your choice. Once you are done with the land, the platform asks questions about your hobbies, lifestyle, and what kind of design appeals to you. In turn, Atmos guides you throughout every step of the process, simplifying complex jargon while educating you about your options.

Another great example of vertical integration is Homebound; they have developed software that allows you to access one centralized tool to manage all transactions and monitor progress when building your next home. That simplifies the entire process and brings transparency, whereas before, you needed to rely on project managers (if you could afford them).

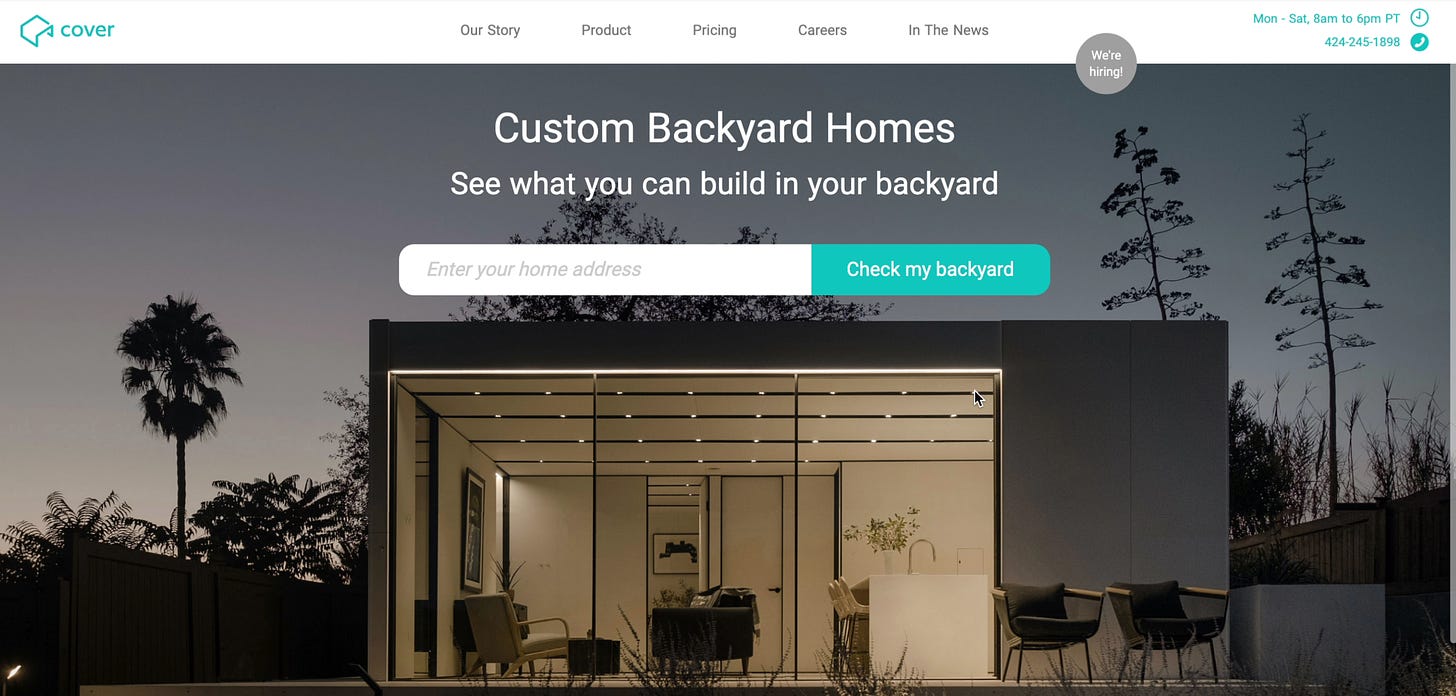

Backyard homes by Cover - Cover handles zoning research, design, permitting, manufacturing, project management, installation, plumbing, electrical, fixtures, and finishes using a fixed price for the entire project. That’s exactly what Keith Rabois meant by vertical integration plus productizing the service. One platform that manages everything for you, all you need to do is to pick the right package/backyard home. Other examples in that space include Plantprefab, Blockable, Juno, and Module Housing, to name a few.

Did you know that the DIY home improvement market is $46B, covering 38% of all home improvement projects? Well, Outfit has built a smart concept to address that market. They have unbundled architectural drawings into step-by-step directions. If you are a non-design person, that’s like translating Mandarin to English.

Apt is another great startup that created a standard pre-development package consisting of design, engineering, financing terms, permitting documentation generation, construction instruction, and prefabrication (i.e., productizing construction). Basically, Apt develops multiple copies of the same building project, similar to how software works, with high upfront costs followed by high margins. In the process, they can reduce costs by over 20% and the development timeline in half.

Opportunities in construction

Here, I would like to highlight once again the massive size of the market. We are looking at the housing market reaching $33.6 trillion in the United States alone. Even smaller niche opportunities in the housing market, like the DIY home improvement market, comes at $46B. Yet, we still do not have any well-known large tech players in the construction space. One can argue that WeWork attempted to integrate the shared office space vertically. After all, they hired world-renowned architects and managed nearly the entire end-to-end experience. Yet, the startup seems to has failed to build a viable business even though, at some point, it reached a $47B+ valuation.

Marrying the best of both worlds, i.e., the combination of high capital expenditures and potentially software-like margins, has the potential to result in huge businesses.

Productizing architecture services

Given the graph presented above about Apt’s model, traditional architecture firms are positioned in the stage of design and engineering and bespoke buildings. Meaning, architecture firms typically are removed from the end-user and deal directly with the investors/financial backers of the project.

Productizing the construction process presents opportunities for architects to deal directly with the end-user, which in the past was limited only to the hospitality and retail industries. In turn, that provides a better experience for the customer due to streamlined communication. Moreover, it empowers the architect to have access to consistent feedback, not only during construction but in the years to come when the project is completed, so they can keep learning and improving.

“For one, it aligns the interests of the architects with the interests of the end user of the space, something that was shockingly lacking in traditional practice.

What most excites me about architects being embedded within a company is to reconsider to whom they are delivering value: ultimately it should be about the end user experience, not the financiers. “

#3 - What Vertical Integration Means for Architects by William Wong

Construction Software

“Six decades into the computer revolution, four decades since the invention of the microprocessor, and two decades into the rise of the modern Internet, all of the technology required to transform industries through software finally works and can be widely delivered at global scale.”

Why Software Is Eating the World by Marc Andreessen

While there are tools and platforms designed for the construction sector (think of Revit and Autocad), the industry cannot compare with the number of tools developed for graphic design and product management professions. People in the tech sector have such a wide variety of great tools at their fingertips, which increases the whole sector's productivity. On the other hand, in construction, there are fewer yet more complicated tools.

“Take the current industry standard for building modelling and construction documentation, Autodesk Revit. In trying to be a comprehensive building design suite all parts of the design process, it has become a bloated piece of software that does no particular thing well.”

#3 - What Vertical Integration Means for Architects by William Wong

I expect to see a lot of unbundling and re-bundling of the large legacy software in construction, followed by the emergence of tools like Canva and Figma but tailored to the building space. Tools with better user experience focused on solving all niche jobs in construction. In turn, such tools will be more user-friendly, having a higher appeal to all parties involved in the process, especially the end-user.

Reference list:

Built stuff by William Wong on What vertical integration means for architects?

Construction physics by Brian Potter on Why it’s hard to innovate in construction?

Austin Vernon on So, you want to build a house more efficiently