Newsletter #44: how to kickstart a marketplace?

14 minutes reading time. Thoughts on startups, growth, and technology 🚀

Welcome to another edition of the Struggle.

The Struggle is a weekly newsletter where I share my thoughts and learnings from running a fast-growing startup in Southeast Asia.

Running a B2B marketplace, I have been thinking of writing my thoughts on what it takes to kickstart a marketplace model for a while. Last week I had a conversation on the topic with a friend who is considering starting one, hence the inspiration behind today’s essay.

Marketplaces are particularly difficult because it feels like you are running two to three businesses simultaneously, i.e., managing sellers (supply), buyers (demand), and everything in between.

“A marketplace connects many suppliers to many buyers, typically enabling them to transact with one another and taking a fee for enabling the connection. But since marketplaces create value by aggregating supply and demand this creates the “chicken and egg” problem.”

Over the past 5 years, I have been involved in marketplaces ranging from photography, budget hotels to professional services.

As more marketplaces become successful (e.g., eBay, Craiglist, Uber, Airbnb, Lyft, Instacart, Lime, etc.), there are many great articles written on the topic, I will do my best to consolidate learnings with this article.

The chicken and egg problem

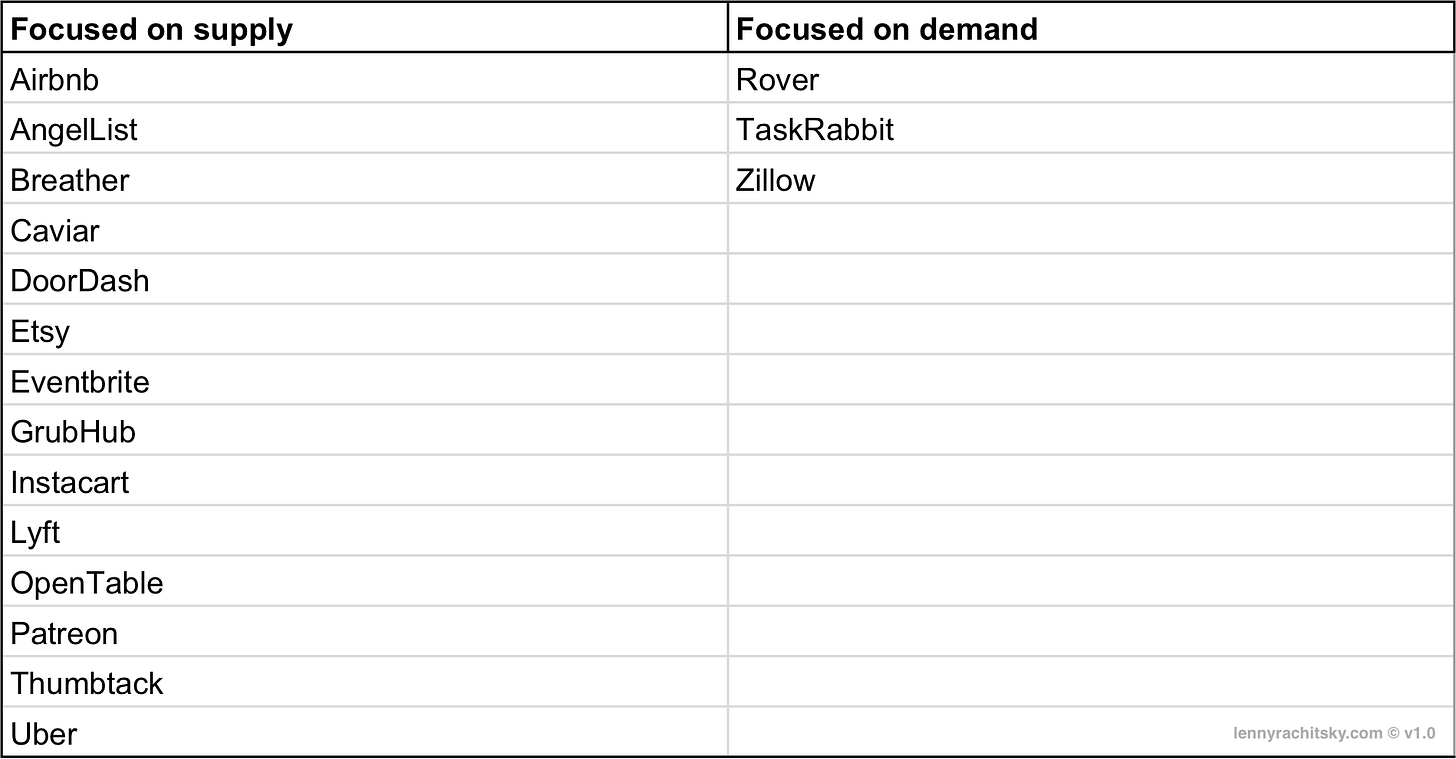

In my experience, most startups focus on solving the supply side in the beginning, as it’s typically easier to get on board.

Who would not want more business?

Yet, there is the counter-argument that you need to solve for the harder side because the harder side will inevitably bring more of the opposite.

Following that chain of thoughts, some startups focus on securing a critical mass of buyers, and then it’s relatively easy to acquire the sellers.

Every business is different, and it’s hard to generalize, but here you go how most marketplaces have done it:

Driving supply

While I am focused mainly on strategies for driving the supply side, many of them are highly applicable to the demand side as well.

Build a community - easier said than done, but if you can grow a healthy and vibrant community, you will find an inexpensive solution to solve for the supply side. In fact, building a community can be applied equally well for the demand side too. It can be done via an online (Slack, Facebook, WhatsApp) or offline (meetups, conferences) medium.

“To launch a city, we’d travel there and hold a meetup. Here in San Francisco, it’s not a big deal to meet a founder. In other places, that’s pretty novel. They would get so excited that they met us that they’d tell their friends. The markets started turning on, and we religiously focused on making sure customers loved us.”

Brian Chesky, CEO and Co-Founder of Airbnb (source)

Single-player mode - building software for the supply side.

“OpenTable’s seeding strategy is what Sangeet Paul Choudary calls Standalone Mode and Chris Dixon calls “Single Player Mode.” OpenTable sold software to restaurants that created value for them without requiring any diners on the “buyer” side of the marketplace. They built unique table management and CRM product (the “Electronic Reservation Book”) and charged a subscription fee for the service. The initial benefit to restaurant customers was the software. Once OpenTable acquired hundreds of restaurants in a city, they started to have a compelling diner value proposition.”

Chris Dixon, Designing products for single and multiplayer modesFind aggregators - unless you are working on a marketplace with a fragmented supply side, there must be aggregators of “sellers” you can tap into. For example, if you are building a marketplace for freelance developers, you can go to university campuses teaching computer science. If you are setting a marketplace for a particular type of food, you can visit food courts.

Scrape listings - you can do it manually by going to platforms like “Craiglist” and scraping relevant suppliers to add to your platform or build a web crawler that can do that for you. This works well if there is an online platform where the sellers have consolidated to an extend.

“At my own startup, SkillSlate, we tried to hack the supply side. We were trying to roll up the long-tail of local service providers who didn’t have their own websites, and we created what we thought was a novel hack. We crawled the web, looked at classifieds listings advertising their services and then we built structured online profiles for these service providers. And then we effectively invited them to claim their listings that they didn’t even create.”

Brian Rothenberg, VP & GM, EventbriteGet buyers on board - it’s relatively easy to go to a vendor and tell them that you have a client who will buy immediately from them if they join your platform.

Offer landing pages - most SMEs have crappy websites. If you can create a simple yet much nicer web experience, many vendors will be eager to join the platform.

Business development - you can hire a sales team to identify and sign agreements with sellers, that approach is slower, but it works well if your supply side is fragmented.

“Supply growth was all sales - door to door, walking into restaurants during their downtime, talking to owners. It was very sales driven. What we did was take every excuse they had for not using GrubHub, and removed it as an obstacle. Fast forward to a couple of years later — you only pay when you receive orders, there are no hidden fees, you can cancel any time. We got to a place where there was zero downside to sign up and to give it a try.”

Casey Winters, ex-growth at GrubHub, CPO Eventbrite

Referrals - this one is pretty straightforward. Many startups design programs to incentivize referrals and grow the network organically.

“Referrals and ambassador programs were big for us early on. Double digits of %’s of new supply early on came from these programs. We went after students because our primary audience was younger and millennial. Some students made so much they had weekly lobster dinners. The pitch to students was to get some work experience and make some money. We had tiers of rewards -- the top tier was essentially a part-time job. As a reward at the top tier, we gave you a letter of recommendation from the COO of Lyft, which many students valued very highly, and was very cheap for us. Referrals (online program) was more impactful top-line, but Ambassadors (people referring users on the ground) were key piece to the launch strategy in each city -- seeding supply and demand ahead of launch. We were able to reduce overhead when launching a city this way, by getting the word out early.”

Benjamin Lauzier, Senior Director of Product - Pro & Marketplace at Thumbtack

Distance between supply and demand

Each model comes with implications on how you need to think about your geographic location. For example, companies like Upwork will see transactions worldwide, while Tinder will see two people dating within the same city.

My personal opinion is that you need to start small and focus on a niche. Only when you are certain that you are creating value for both supply and demand can start scaling to other geographical locations. Especially if you are a high-density marketplace.

“…the ultimate success of your marketplace will depend on your ability to create meaningfully more happiness in the average transaction than any substitute, not how many transactions you accumulate.”

Sarah Travel, General Partner at Benchmark

Essentially the 3 tips here are:

Focus on a geography

Focus on a niche community

Focus on a vertical - some marketplaces start with multiple verticals, but I am a big fan of starting small, learning one vertical inside out, and only then venturing into others.

Do things that do not scale

In the past, I wrote an article on why it’s important to do things that don’t scale.

It basically refers to avoiding to automate processes too early in the process of building a new business. You need to throw people at the problem until you have enough scale to reduce the manual requirements.

It would be best to ignore the startup mentality that you have to solve problems in a scalable way. Instead of writing a few lines of code that can solve a problem for anything between 1 to 10 million customers, you need to do things that do not scale. Because that helps you truly understand the problem you are solving, the workflows, and how to build a great solution.

“An example of scrappiness Tony always gives is the Cheesecake Factory in the Macy's building in San Francisco. The reason we won the Cheesecake Factory — it’s on the sixth floor of the mall, by the way — is because we had dashers just dedicated to running up and down the elevator to handoff the food, instead waiting for a dasher to park. That’s one example of us going the extra-mile, operationally, and doing things that don’t scale.”

Micah Moreau, VP at DoorDash

Connecting supply and demand

Most marketplaces invest a lot of effort in controlling the entire experience of bringing the service/product to the buyer. Founders are aware that if they do not control most of the experience the service can be ruined by things outside of their control. Examples of that can be seen in how Postomates and Doordash deliver food, picking it from the restaurants that do not deliver, thus injecting their brand and experience wherever possible.

While that’s risky for some verticals (e.g., UberEats may control most of the drivers in the market), it helps each startup to create brand awareness and to have tight control of how each product/service is delivered.

Stitching it all together

Most marketplaces focus on supply early on. Yet, do consider that once you have a critical mass of sellers, you will need to focus on the harder side, which in most cases, is the buyers.

Focus. Start with one geography, focus on a niche community, and master one vertical before scaling.

Do things that do not scale. That’s the only way to understand the problem you are solving truly.

If possible, create an end to end experience to ensure standards of service and boost brand awareness.

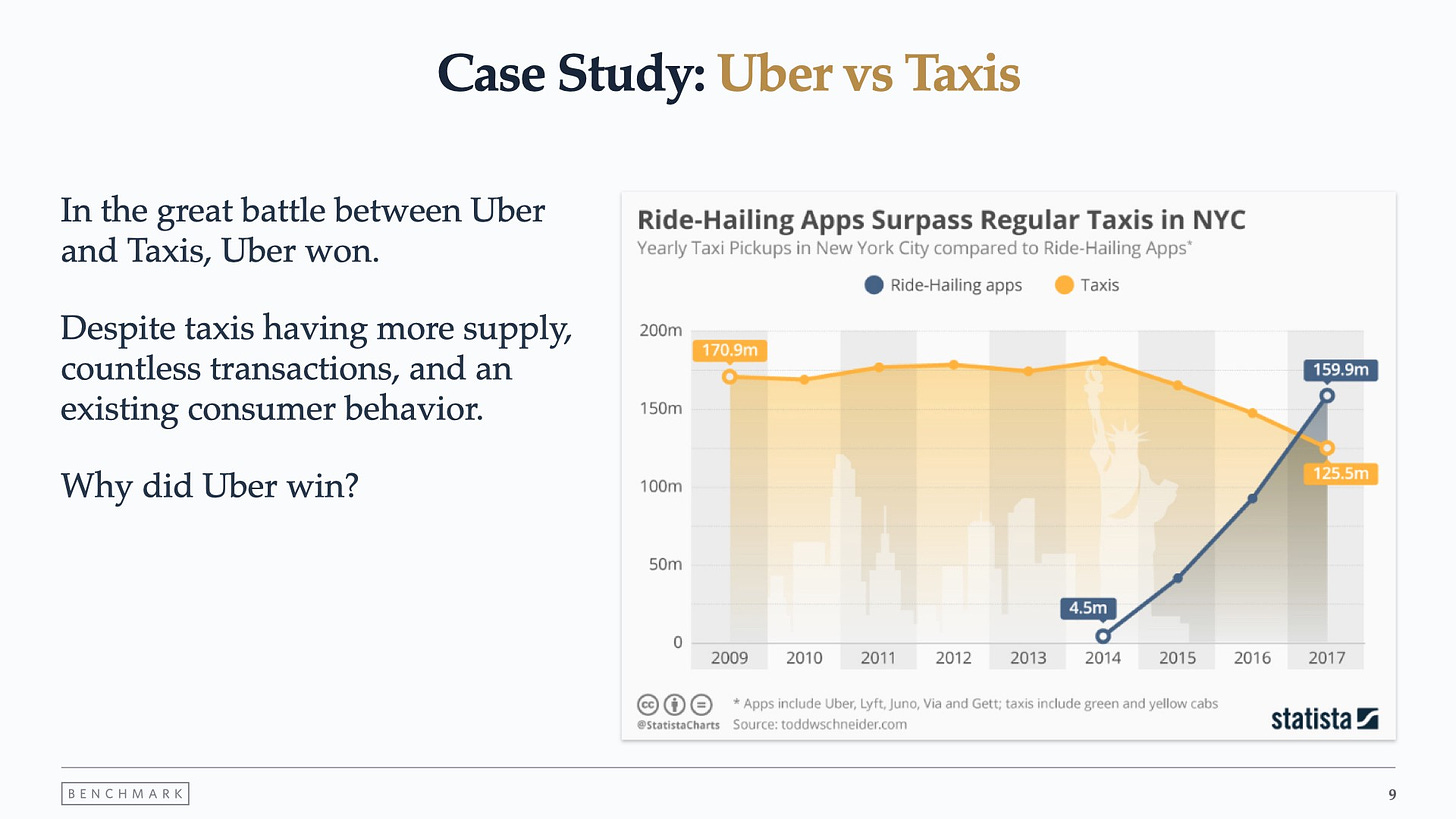

I will finish the article with this case study of Uber VS Taxis as I think it shows what’s truly important when building a marketplace.

“Uber won because buyers and suppliers do not care how big you are. They care how happy you make them vs any substitute.

More efficient and stronger matches, better economics, more trust, better experience.

Building a marketplace is a relentless pursuit of exceeding expectations to create happiness.”Sarah Travel, General Partner at Benchmark

Inspiration:

Paving The Way To Marketplace Liquidity by Brian Rothenberg and Casey Winters

Liquidity hacking: How to build a two-sided marketplace by Josh Breinlinger

How the 100 largest marketplaces solved the chicken and egg problem by Eli Chait

How to Kickstart and Scale a Marketplace Business by Lenny Rachitsky