tl;dr

- Trust is not binary. It's a spectrum. Some societies trust easily. Others don’t. You can literally map it.

- There's a strong positive correlation between trust and GDP. High-trust societies grow faster. Low-trust ones stay stuck.

- I was born in Bulgaria (low-trust), moved to Denmark (high-trust), then worked across Southeast Asia (mixed, but mainly low). You feel the difference instantly.

- In Denmark, people trust first. It's liberating and efficient. In Indonesia or India, you earn trust painfully, inch by inch.

- High-trust environments create speed. Low-trust environments create drag.

- When you expect good intentions, you collaborate faster. When you expect bad ones, you move slowly, double-check everything, and spend half your energy covering your back.

- Early in my career, I trusted easily. Locals thought I was naïve. I got burned sometimes. But overall, trusting fast paid off a lot more than it cost me.

- Distrust feels smart in the short term. It feels strategic. It feels like you’re protecting yourself. Long-term, it’s a tax that costs you building relationships with good people.

- Suspicion drains creative energy. It kills autonomy and agency. It creates cultures where no one builds unless someone is watching.

- People from high-trust cultures need to build some muscle for dealing with low-trust environments. Don’t take suspicion personally.

- People from low-trust cultures need to realize that world-class talent will avoid them if they keep defaulting to suspicion.

- You cannot hire top performers while treating them like potential liabilities.

- Trust will be abused. That's the price of playing at scale. You will lose sometimes. But overall, trust is a positive-sum bet in a world that rewards compounding.

Trust isn’t binary. It’s a spectrum. Some cultures are high-trust societies, others are low-trust. Luckily, it's a topic that has fascinated many people for decades, so we have plenty of data.

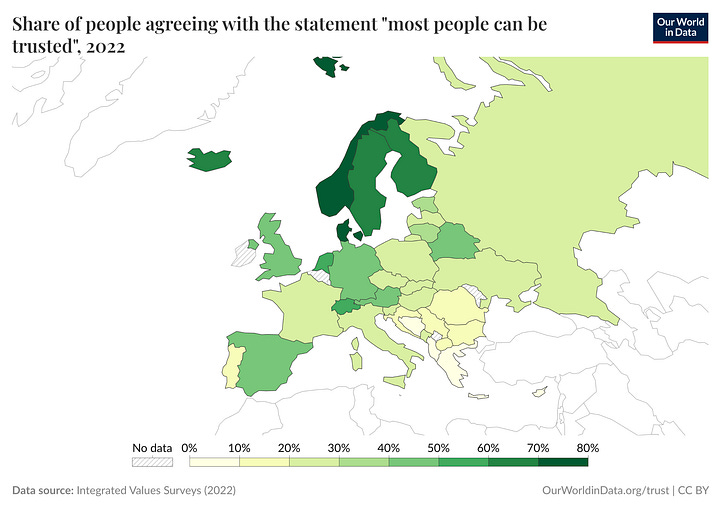

In the map below, you’ll see trust levels across different regions (the darker the color, the more people trust strangers).

Scandinavian countries lead in trust. Meanwhile, many parts of South America, South Asia, and Africa show only 10% of respondents saying “most people can be trusted.”

Why does this matter?

For one obvious reason, trust and economic development are tightly linked.

Kenneth Arrow, Nobel laureate, wrote in 1972 that "virtually every commercial transaction has within itself an element of trust." The data backs this up: when you chart trust against GDP per capita, the relationship is strong and positive. High-trust cultures build wealth more easily; low-trust cultures struggle.

But data is one thing. Living it is another.

I’ve had the chance to work across the trust spectrum. I was born in Bulgaria, one of the least trusting nations in Europe. Growing up there, you learn to lead relationships with skepticism. Distrust is the default. Trust must be earned.

Later, I moved to Denmark, where the default was the opposite. People trusted freely, even a foreigner like me. It was liberating. High-trust cultures assume goodwill, transparency, and collaboration. When someone betrays that trust, it’s shocking precisely because it’s so rare.

After Denmark, I spent a decade living and working across Southeast Asia—Indonesia, Singapore, and India. These are countries where trust is much lower, and the difference is palpable. Interactions often feel defensive, transactional, and cautious. In low-trust environments, suspicion isn't personal; it’s structural. Corrupt legal systems and weak institutions have trained people to be careful. Zero-sum thinking dominates.

If you’re trying to build something big, like a startup, low-trust dynamics are a tax you can’t afford.

When you come from a high-trust environment, you walk into meetings assuming positive intentions, openness, and mutual benefit. In low-trust environments, that naivety can be a liability, and locals will not hesitate to call you a fool for it. I know, because I’ve experienced it.

I remember my early jobs in Indonesia, where locals were confused about how much I trusted new hires. Over time, I learned to recognize that while trust is good, blind trust isn’t. Environment matters.

The best founders I know, irrespective of where they’re from, learn how to adjust their trust filters. They’re not permanently suspicious, nor are they permanently naïve. They read the room. They know when to lower their guard and when to raise it.

This lesson crystallized during a job interview years ago. I was interviewing for a startup headquartered in Singapore, led by a team largely based in India. The process was long, with five stages, a case study, multiple rounds, and the atmosphere throughout was distrustful, to say the least. Every conversation felt like a test of my integrity. By the time they offered me the role, I already knew I would turn it down.

When trust doesn’t gradually build, when suspicion lingers even after evidence of alignment, the relationship is doomed to fail. No amount of compensation can fix a broken foundation.

The founder I interviewed with, likely didn’t realize how toxic the process felt. In his environment, skepticism was normal. But to me, it felt corrosive. And this disconnect is not rare, it's something I’ve seen over and over across Southeast Asia and India.

The cost of low trust is too high. It slows deals. It increases due diligence and verification costs. It makes hiring capable, high-autonomy talent much harder. And ultimately, it limits how fast an organization can move.

So, I wonder: does low trust have any value?

In harsh, unpredictable environments, being cautious probably kept families alive. Distrust may have been an adaptive strategy.

But for builders, for people trying to grow things fast, low trust is like carrying a heavy backpack while running a race. You may avoid getting scammed, but you move slower.

Reflecting further on these experiences, I realized the solution might lie in a hybrid model.

Founders must learn to calibrate trust. Start cautious but quickly escalate to high-trust modes when dealing with credible people. Skepticism is useful defensively; trust is essential offensively.

Without enough trust, you can’t build strong teams, move fast, or create positive-sum outcomes. Without enough skepticism, you get exploited. Good leaders know when to switch gears.

If you’re job-hunting in a low-trust culture, don't take suspicion personally. Study how great local players strike a balance between caution and openness. And make sure you experience at least one high-trust, fast-paced environment in your life; it will recalibrate your expectations permanently.

If you’re a founder from a low-trust environment, consider this: building a world-class team eventually requires you to either bring people from higher-trust cultures or build such a culture yourself. If your default posture is distrust, you will lose some of the best talent before they even sign the offer letter.

At scale, low-trust environments create friction that slows down everything.

The best builders understand that trust isn’t naïve. It’s a force multiplier.

“People break into two buckets. Some come at life as a series of transactions. And some people come at life as about building relationships.

You can have a successful life doing transactions, but the only way to have a great life is on the relationship side.”

— Jim Collins

This is a great piece